Operation Prawn: Attacks on Line of Rail: Barragem to Malvernia: August, 1976

Reconnaissance teams dropped in by free-fall parachuting and by helicopters along the line of rail, confirmed information:to hand that ZANLA were making extensive and ever increasing use of Mozambique Railways to move large numbers of terrorists from Barragem to Mapai, and on to the border town of Malvernia, from where they would infiltrate into Rhodesia.

The use of the railway had shown a marked increase after we had destroyed or captured the bus fleet, previously used for moving terrorists to the border, during the Mapai raid.

The FRELIMO garrison at Malvernia had been reinforced and they were adopting a markedly more aggressive attitude towards the Rhodesian troops based in the little village of Vila Salazar, which was within shouting distance across the border. Frequently, whenever they got jittery or felt they had a surplus of ammunition to waste, they mortared and shelled the village.

The Rhodesians were ordered to keep their heads down, but not to retaliate… in case it escalated the war! I discussed the information our reconnaissance teams had brought in with the Special Operations Committee (SOC), and also the provocative situation pertaining at Vila Salazar.

I urged that the Selous Scouts be allowed to cross into Mozambique and demolish the railway line piecemeal in a series of raids. The initial reaction, by some, to my proposals was tinted with a certain amount of horror, and one officer accused me outright of being a war-monger engaged in deliberately trying to escalate the conflict.

“The railway is an economic target, not a military one,” I was told. I dug in my heels and pointed out the tonnage of war material and supplies one train could deliver right up to our own doorstep, which hardly kept it in an economic category. The final decision which was arrived at after considerable argument and a lot of recriminations, was that we could mount attacks on the trains along this route, but only when ZANLA were actually seen to be using them.

Then, a few days afterwards, some unusually large gangs of ZANLA terrorists were bumped well inland by Security Forces, and it became crystal clear to even the most cautious of those on the Special Operations Committee that they had come in via Malvernia… so… they threw caution to the wind and ordered us to neutralize the line.

I tasked Major Bert Sachse, commanding the fort at Chiredzi, to forthwith commence a concerted effort against the track. He did, but the general topography there… it was featureless and flat… did not lend itself to his sabotage efforts. There were no bridges or culverts in the area, so effecting repairs to damaged tracks was simplicity itself.

He sent in small teams by helicopter along the line of rail, but apart from two nicely successful train derailings, the whole exercise was virtually profitless.

We sat down in conference and reviewed what had been done, and what could still be done. Then we thrashed through the problem again until we finally concluded that the answer was to blow the track and derail at least three trains at different places along the line. Then, take out the only steam crane in Mozambique when it came from Maputo to crank the carriages back onto the repaired track. We felt that with three wrecked trains, with long intervals between them and the means of clearing the line reduced to scrap iron, we would have achieved our objective.

Because of the waterless terrain and the sandy nature of the veld in that part of Mozambique, which made anti-tracking virtually impossible, we were able to deploy the teams tasked with the demolitions only by helicopter.

Lieutenant Richard Pomford was detailed together with a force of seven men for the first strike. Much time was spent with Rhodesia Railways, studying the construction of diesel locomotives, so the RPG-7 gunner would know where to place his shots for them to be the most effective.

An observation point was established on the water tower at Vila Salazar and kept there for several consecutive days, so a timetable of train movements across the border could be compiled. The plan was for the ambush party to move by helicopter to a pre-selected dropping zone, twenty kilometres south of Malvernia and ten kilometres west of the railway line, and then to move at best possible speed to the line where they would lie up until ready to mount their attack.

The biggest problem they faced was that the line was being patrolled at frequent but irregular intervals by FRELIMO, so they couldn’t risk laying the charges too far in advance of a train’s appearance in case they were discovered.

The observation post on the water tower at Vila Salazar would keep radio contact with Richard and tell him the moment a train left Malvernia. Then, when the train was heard approaching by the ambush party, they would move forward and take up position. After judging by guesswork when the train had reached the critical point, but was still far enough away for the crew not to spot the happenings ahead, two Scouts would quickly set the charges on the rail, and get back in cover.

If everything went as planned, then, as the train ground to a halt after the detonation had derailed it, the RPG-7 gunner would immediately fire two rockets into the locomotive’s vitals to ensure it would never move again.

It worked perfectly so far as timings were concerned… but that was the only thing that did! For, as the demolition party were about to set their charges on the rail, a FRELIMO bicycle patrol suddenly appeared.

It was too late to place the charges by the time the patrol had passed, so Lieutenant Pomford decided to rocket and machinegun the train as it passed his position. One rocket scored a direct hit on the locomotive, but it missed all the vital spots, so it rumbled on by, our men firing long bursts of automatic fire into the carriages.

It was not a long train… a mere three carriages… and as the rear one drew parallel with the ambushers, they were subjected to a nasty surprise for it was sandbagged and manned by three FRELIMO soldiers armed with heavy and light machineguns, with which they returned a heavy and sustained fire from almost point-blank range, which continued until the train disappeared from sight around a bend.

Richard and his men hugged the ground as the hail of bullets thudded into the earth and sung through the bush around them. Fortunately, they suffered no casualties, but it was a very close call indeed. They did not wait to make a post mortem of events, but legged it back to the dropping zone to call for the helicopter to uplift them, so they could get clear before the FRELIMO converged onto their tracks.

It was a group of very disappointed and despondent Scouts who climbed from the helicopters back in Rhodesia and reported what had happened to Major Bert Sachse who was awaiting them. Their already edgy tempers were not improved when the local Brigadier strolled up and eyed them distastefully.

‘You failed in your mission, didn’t you?’ he said. Lieutenant Richard Pomford came close to insubordination, but frankly, I didn’t blame him in the circumstances.

Ignoring the triumphant criticism which came to us from that and certain other quarters, we sat down again and re-studied the problem in the light of our recent experiences.

The observation post on the water tower at Vila Salazar, was kept in operation and the men performing this duty, reported noticing that every Tuesday morning an Alouette helicopter, painted yellow… the Rhodesian Air Force were also equipped with Alouette helicopters… flew up the line of rail to the Malvernia rail and road junction, from where it would then fly north-east and follow the powerline to the Troposcanner some twenty five kilometres away.

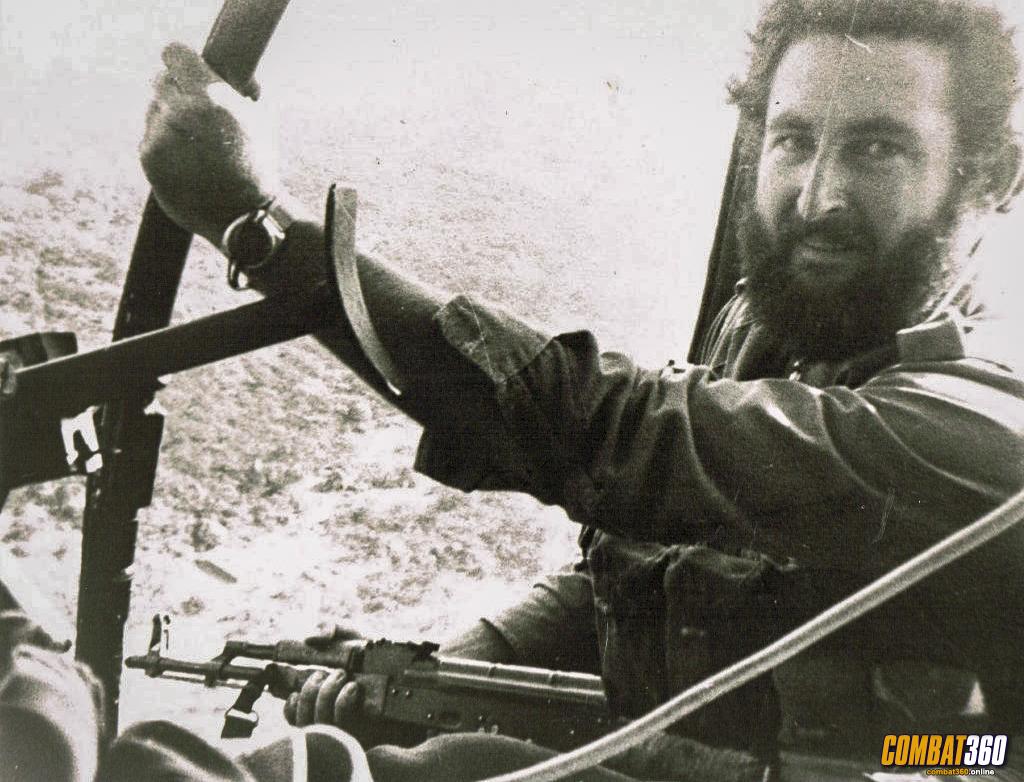

Derek Andrews whilst serving with the Selous Scouts, aboard a French manufactured Aérospatiale Alouette helicopter returning from a successful operation in the Hot Springs region of south-east Rhodesia. Photo: Derek Andrews / Victor Harbor RSL

We checked radio intercepts to ascertain the purpose of these flights and discovered it was carrying an engineer from Maputo, on a weekly line inspection. The flight was always preceded by a radio warning telling the FRELIMO troops on the ground not to shoot it down. The yellow paint used made it easily distinguishable from the camouflage of its sisterly but more meanly aggressive Rhodesian war planes.

I spoke to the Rhodesian Air Force and as a result one of their helicopters was spray-painted a delightful canary yellow and for several weeks, while it wore this gaudy plumage, we were able to drop our reconnaissance sticks into Mozambique with total impunity, until one day the FRELIMO suddenly tumbled to what we had been doing and reacted with an angry fusillade. We called it the yellow submarine.

FRELIMO quickly built up an extensive patrol system which made it difficult to get near the line undetected and several of our patrols had very narrow escapes.

As a consequence, all sorts of ploys were used to throw the FRELIMO off balance. On one occasion we prepared two sets of explosive charges and two helicopters were ordered to stand by. Contacts in the internal operational areas were happening daily and as soon as the next one was concluded, the body of a dead terrorist was collected and rushed by air to the Scout team standing by waiting for it.

It was stripped, re-clad in Security Force camouflage and loaded in one of the helicopters, both of which then took off… each heading for different preselected spots on the railway line.

Bert Sachse and one Scout dropped down and unloaded the dead terrorist… now an unknowing and unprotesting pseudo member of the Security Forces. They set up a demolition charge on the track between the lines… so the explosion wouldn’t damage the track and stop the next train … and then laid the body on the charge. They lit a short delay fuse and immediately re-emplaned in the helicopter and flew back to Rhodesia… their part in the operation was completed.

The other helicopter had meanwhile dropped off the second team further down the line where they took cover and waited.

Shortly afterwards they heard the dull thud of an explosion up the line. As hoped, FRELIMO patrols from the whole sector immediately homed in towards it, and found exactly what we had intended them to find at the scene of the explosion… torn fragments of Security Force uniform and mangled bloody flesh… but the line was undamaged. It was clearly the work of a Rhodesian saboteur who had accidentally, due to incompetence, blown himself up while preparing the charges.

Scattered around the area they discovered some terribly interesting, although unbeknown to them, bogus documents. The FRELIMO, wildly excited at having at last found some tangible evidence of Rhodesian involvement, gathered up what they could and rushed off en masse to the Nearest post to report their findings, each intent on claiming credit or getting some of the reflected glory, leaving the line unprotected for the arrival of the next train which, needless to say, the second patrol promptly blew off the rails.

A few days after this, Bert Sachse again entered Mozambique and laid charges along eight hundred metres of railway line.

Just prior to detonation a train unexpectedly appeared from the direction of Malvernia. They attacked and set the diesel locomotive ablaze, the intense heat seizing its wheels and rendering it immovable… and so it remained where it was for the rest of the war, very effectively blocking the line so that no trains could run into Malvernia.

After this, supplies had to be transferred to trucks at the rail blockage point and taken by road to Malvernia, which put an immediate and impossible strain on FRELIMO’s transport system.

At about the same time, to further add to the misery of FRELIMO and ZANLA, another team consisting of Lieutenant Tim Hallows, Piet van der Riet, Peter McNeilage and Sergeant George… all wearing FRELIMO uniforms… went into Mozambique with relative impunity in the yellow submarine helicopter, piloted by John Blythewood, and were dropped without incident on the line of rail between the power lines and Chicualacuala.

They stayed under cover while a train passed by on its way to Malvernia. Rob Warracker, in a Lynx aircraft flying at high altitude, well away from the scene of the impending action so as not to arouse suspicion, watched the westward progress of the train which was pulling several large water bowsers as well as carriages… bowsers were the only means by which Malvernia could be supplied with water.

The demolition team set their charges, took up ambush positions and waited. At 15h00, Rob Warracker warned them from the Lynx that the train had turned around and was On its return journey with empty bowsers and loaded coaches.

The locomotive was travelling fast and the explosion derailed it in a screech of agonised metal. The ambush party were horrified as it careened through the bush at them stopping only just short of their position. Peter McNeilage only narrowly missed being crushed to death by it. The coaches were packed to capacity with FRELIMO troops, and many of them were killed or injured in the derailment. The survivors spilled from the wreckage… some dazed and stunned… others shouting or screaming in panic or pain.

The ambush party having nearly been overwhelmed by the train, were forced to abandon any ideas they had of putting in RPG-7 rockets as a coupe de grace and were forced to sprint from the scene in relative disorder to avoid a follow-up, but fortunately, the FRELIMO were far too demoralised and shattered to give pursuit a thought… self preservation and survival was foremost in the minds of the uninjured… and most, unwittingly, chose the same direction of flight as the ambush team.

Peter McNeilage, leading the team’s disorganised retreat, glanced over his shoulder and saw to his horror, that not only was the surrounding bush alive with FRELIMO bent on putting as much distance as possible between themselves and the train, but that two of them were only five or six paces behind Piet van der Riet… unbeknown to Piet.

Shouting a hurried warning to Piet van der Riet, Peter McNeilage turned and snap-shot both of the enemy, causing all the fleeing FRELIMO to tur and run in the opposite direction. Rob Warracker, from his lofty perch, called for the return of John Blythewood’s yellow submarine. John dropped into a very small landing zone indeed to pick up the team, tipping his rotors on the surrounding bush as he landed, but in spite of this, he managed the uplift and got back to Rhodesia safely.

Soon after this we heard from radio intercepts that large contingents of ZANLA terrorists had been shipped down the east coast from Dar-es-Salaam in Tanzania, and were being held at the small coastal town of Xai Xai. On hearing this, we re-doubled our efforts to neutralize the railway line between Barragem and Malvernia. If they were intent on infiltrating Rhodesia, we certainly weren’t going to allow them to do it in comfort.

To the south of Barragem, a road and rail route ran across the summit of a dam wall. An enormous amount of explosives would have been needed to demolish it. To double our difficulty, this dam was sited actually on the outskirts of Barragem itself, which was by then a FRELIMO brigade headquarters, so the possibility of us placing large demolition charges in position without detection, was fairly remote.

A bridge to the north of Barragem offered better prospects. It was constructed of steel girders which immediately reduced the amount of explosives required. A close study of aerial photographs revealed the locality had little population.

Additionally, a good dropping zone was close by as well as there being some fine navigational aids, in the way of landmarks, to work by. The prospects for free-fall entry were very good, the only problem still besetting us, was how a two-man team could transport the large amount of explosives required from the dropping zone to the bridge, set the charges and then blast them… all in one night.

Additionally, a good dropping zone was close by as well as there being some fine navigational aids, in the way of landmarks, to work by. The prospects for free-fall entry were very good, the only problem still besetting us, was how a two-man team could transport the large amount of explosives required from the dropping zone to the bridge, set the charges and then blast them… all in one night.

After many long sessions of abortive discussions, the Selous Scouts’ Motor Transport Officer appeared with a triumphant smile on his face and invited me to step over to his workshop. Once there, he unveiled a weird but intriguing looking vehicle resembling a space-buggy, which he and his men had constructed. It had a fairly lightweight frame and had been designed to carry the precise amount of explosives required to blow the bridge.

To give it cross-country capability, they had fitted it with wide fat-tacky tyres and like its Beach-Buggy distant cousin, it was powered by a Volkswagen engine.

With this, the plan became relatively simple. Two men, the buggy and the explosives, would be dropped some twelve kilometres from the target. Once on the ground, the buggy would be assembled from its breakdown kit… it took about half an hour… the explosives loaded and the demolition team would drive it to the bridge. The charges would be positioned and set according to a pre-worked out pattern, and then detonated.

All this could be achieved in one night without difficulty. We took the plan to an advanced stage where dress rehearsals were about to begin, when the Special Operations Committee (SOC) unexpectedly ordered us to abort the plan, because it had finally been decided at top level, that the bridge was an economic target, not a military one.

They were wrong, and it was a great shame as it turned out, for later on in 1979, almost three years afterwards, a large conventional airborne operation was launched to knock-out the communications system in the Gaza Province… both the steel girder bridge and the route over the dam wall featured prominently as targets.

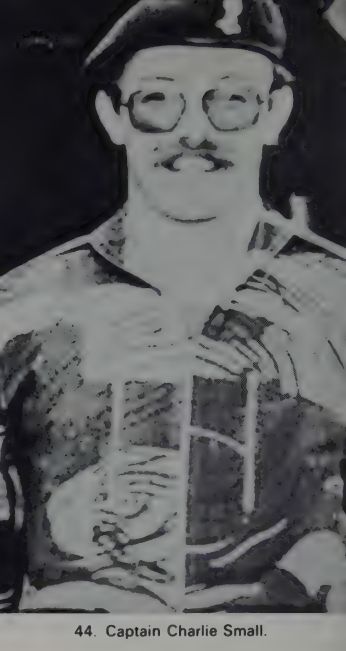

During that attack a helicopter carrying the Engineers’ demolition party, was shot down by ground fire and twelve Rhodesian soldiers… including Captain Charlie Small, Selous Scout and Rhodesian Engineer… were tragically killed.

from Selous Scouts – Top Secret War (Peter Stiff as told by Lt.Col Ron Reid-Daly)