Tank Killers Take on Big Game

A Soviet T-55 battle tank rumbles slowly through the southern Angolan countryside, its two mates in echelon close behind. The FAPLA tank commander peers nervously at every shadow, at every oddly shaped bush and rock. He knows the South Africans are nearby, and he’s sweating not only from the blistering heat, but from fear as well. He calls a halt at the edge of a small clearing, straining to pierce the thick bush on the other side. Twisting in the cramped turret, he hears rather than sees his infantry support struggling to catch up, their gear loose, rifles and equipment catching and breaking scrub branches. The two other T-55s sit idling, oily diesel smoke staining the clear air. The FAPLA commander sighs and turns back to the front, ready to push on. Suddenly, three simultaneous flashes erupted from the tanks’ flank. The T-55 commander didn’t even have time to raise an eyelid before the South African Ratel’s 90mm HEAT round slammed into the turret. He never knew that the other two T-55s under his command suffered the same fate.

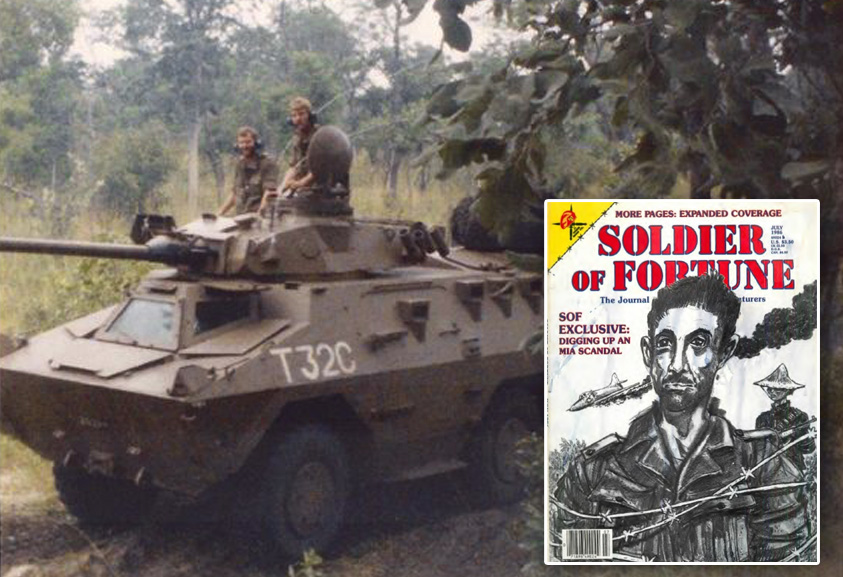

LEFT: Eland 90 Light Armored Car, based on the French Panhard AML, sees heavy service in the operational areas although more emphasis is being placed on the IFV concept. RIGHT: Valkyrie MRL in action

Before the Cuban infantry adviser could even react, the three Ratels had disappeared into the bush, leaving only the sound of their turbocharged diesels – and three burning T-55s – in their wake. Conventional Western light armored fighting vehicles beating Soviet armor? The above incident never took place, but ones just like it have – all over the world. And the outcome is real enough. Infantry Fighting Vehicles (IFV) and Fire Support Vehicles (FSV) can, and do, kill Soviet heavy armor – even in the face of the time-worn axiom, “It takes a tank to kill a tank.”

Ask the Israelis or the South Africans, or the Rhodesians when they were still battling Soviet-supplied armor inside Mozambique. The catch, of course, lies in the level of crew training and tactical employment of the tank-killing weapons. In general, training of Western armored forces is far superior than that of their adversaries; if the reverse were true – watch out.

The Israeli equivalent of a lieutenant colonel, Yoram Nevo, phrased it this way when I saw him last in Jerusalem: “Put a well-trained American crew into an APC or similar thin-skinned vehicle, and that group of soldiers would be no match against an equally well-trained European tank crew. And that includes the Soviets.” He cited the example of two Iraqi tank divisions that were wiped out in a single afternoon in the northern Israeli highlands during the Yorn Kippur War. “Things are a little different in the Third World, in places like the Arab world and Africa. It’s there that the odds are weighted for the better-motivated, better-trained and better-equipped force.” Naturally, Neva counts the Israelis among the latter. Let’s look at a few of the incidents. During the Yorn Kippur War, when Israeli troops and guns were initially heavily outmatched and Israel as a nation was caught by a sneak attack across two fronts (Egyptians from the south and Syrians from the north), there were some recorded Israeli successes of light armor forces versus tanks. Often, heavily outgunned, Israeli crews in thin-skinned vehicles managed to slip through successions of Arab “cordons of steel” – the Egyptian and Syrian description of their armored thrusts. Israeli troops, deployed in captured Russian BTR-152 armored personnel carriers or Israeli half-tracks, usually armed with nothing heavier than 120mm Soltam mortars, managed on several occasions to blast their way out of positions previously regarded as hopeless. Usually they achieved this by laying down a terrible volume of fire. They slammed through supporting troops and forced armor units to pull back, if only temporarily. Sometimes, however, it didn’t work out that way. Ammunition ran out and Israelis were then overrun or taken captive, but many times the ferocity of the Israeli counterthrust was enough to effect a breakthrough. The Israeli secret, according to Lt. Col. Neva and other senior military commanders, rests with the premise: If you’ve got the momentum, then you have the initiative. And, for the Israelis, the premise works.

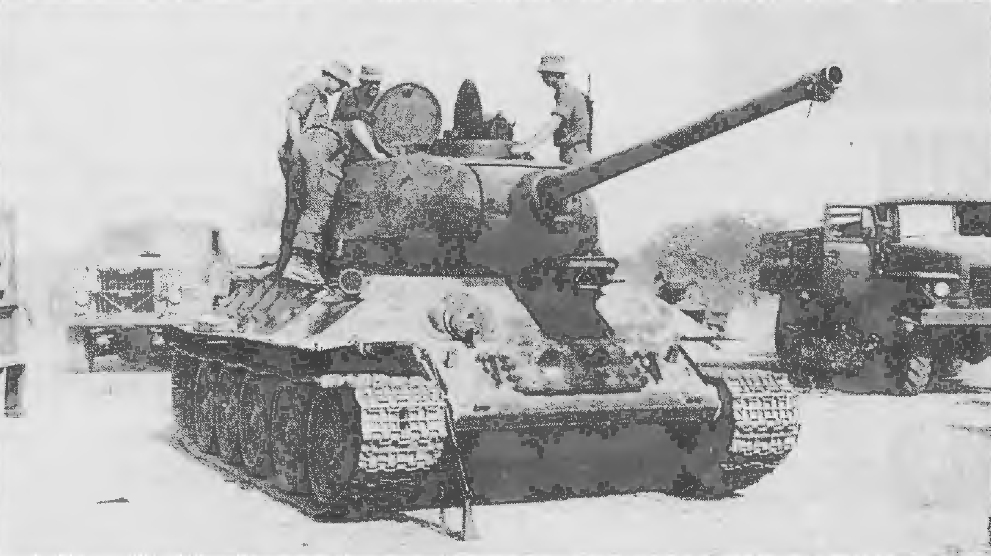

Russian T-34 tank after a short-lived encounter with SADF Ratel.

The South Africans do things a little differently although the concept is basically the same. In almost two decades of fighting inside and along the Angolan border, they have never deployed any of their Olifant (Elephant) Main Battle Tanks (MBT) into that combat zone. They haven’t needed to. Of course, this doesn’t detract from the fact that FAPLA, the Angolan army, does have and use large numbers of Soviet-supplied tanks. These include the antiquated T-34, which still sees good service in many theaters of Third World military activity, as well as a combination of T-54 and T-55 MBTs. The latter are usually armed with 1OOmm D-10T rifled tank guns with a range of just less than 15,000 meters – a distance · of almost nine miles. These have been deployed by Angola’s ComBloc advisers in large (but classified) numbers throughout the southern half of Angola, adjacent to South African positions in northern South West Africa/Namibia. And when Pretoria occasionally decides that the time has come to take out SWAPO (South West Africa People’s Organization) terrorists at their source, an occasional ill-matched confrontation begins between the South Africans and the Angolans.

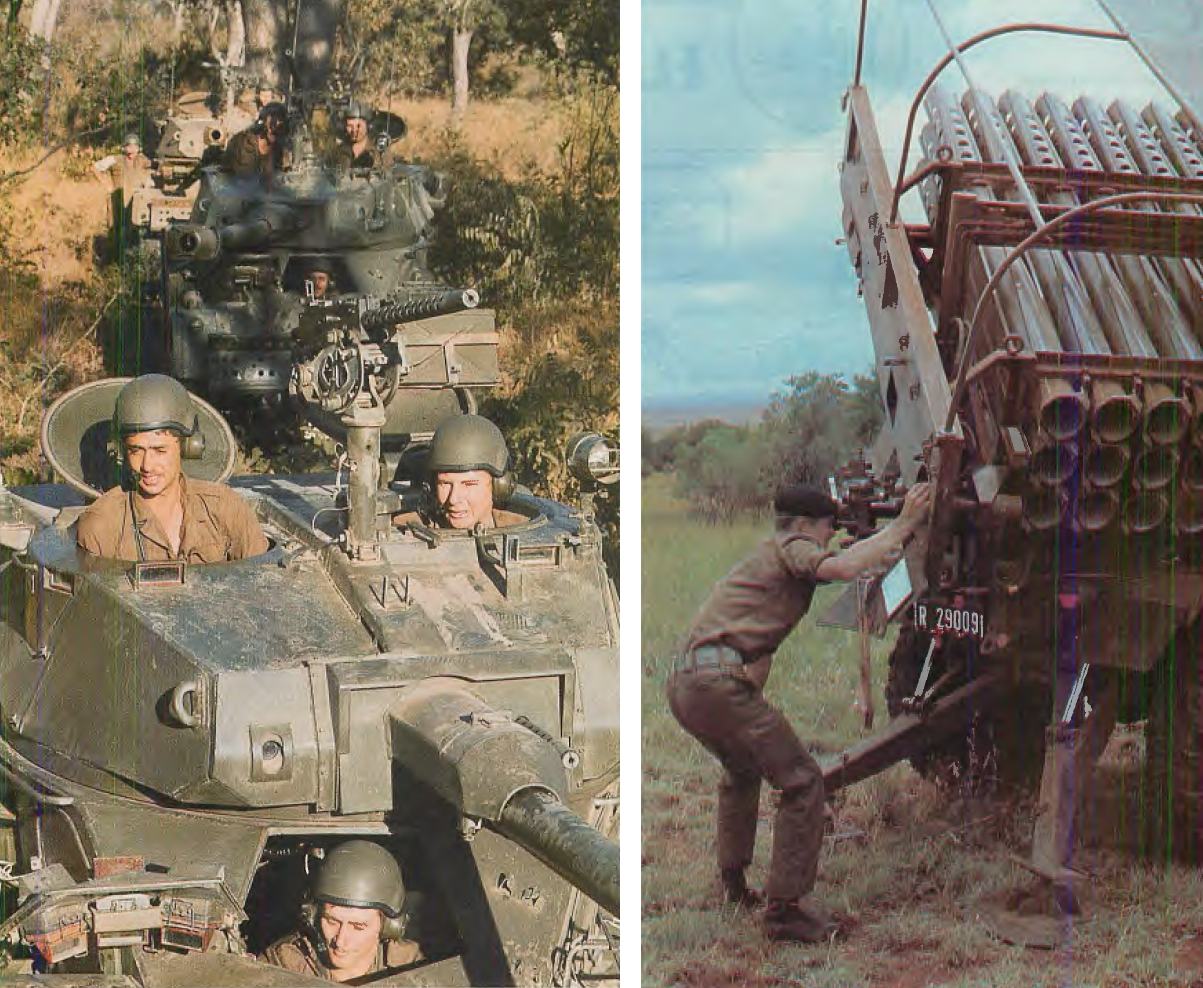

Choppers, Dakota and armored fighting vehicles stand by to move during a long-range penetration into Angola.

There have been at least a dozen well-documented instances of South African light armored vehicles, such as Eland armored cars and Ratel IFVs, exchanging body blows with Soviet armor in this region. To date, the South Africans have knocked out or captured about 30 pieces of Soviet hardware. This tally includes Russian T-34 medium tanks, T-54 and T-55 MBTs as well as the much lighter PT-76 amphibious tank – now appearing inside Angola in unusually large numbers. The reason for this success? South African (and Israeli) strength when using light armor against heavily armored tracked vehicles lies essentially in the mobility of their lighter vehicles. Several Ratel and Eland commanders with whom I spoke during and after Operations Protea and Askari – both incursions into Angola – agreed that they lived to tell the tale of encountering a Soviet-supplied MBT simply because they were able to quickly reverse gears and scurry away to safety in double-quick time. These youthful commanders, most barely over 21 years old, would then probe the tank’s flanks in the hope of pushing a 90mm HEAT shell up their backsides. More than once their efforts were successful.

One young lieutenant I stayed with north of Ongiva told me of his experiences during Operation Protea: “We weren’t away from the main thrust of our force for more than a few hours one morning. Together with three other Ratels – ours had a 90mm gun mounted on the turret – we were probing defenses around a village where reconnaissance units had told us there had been a fairly heavy concentration of the enemy.” Without warning, the light armored force was hit by a ground attack. “An RPG rocket launcher was obviously meant to signal the onslaught, but fortunately the warhead glanced off the sloping turret. The blast was terrific and there was no doubt that we had hit trouble. “I ducked the Ratel behind the village toward a sl ight mound which appeared to be something of a garbage heap. Coming round the flank I almost ran into a T-54 tank, dug into a hull-down position with only the turret protruding. That crew was as surprised as we were, but we didn’t hang around.”

Taking up a position in some thick clumps of bush, he sent one of his men into a tall tree to recon movement around the strongpoint. There was a definite risk that he could have been spotted, but the armored car officer needed the intel in order to formulate his plan. Moments later the man returned. The tank had emerged from its bunker. The lieutenant had to weigh his options carefully. His position was obscured by bush so he was safe – at least for the moment. The T-54 tank crew knew he was in the vicinity, but they weren’t certain exactly where. Both crews knew that the first to get a shot off would win the battle. “So,” the South African said, “we just sat tight.” “We knew, when the battle came, that we would have to fire through some fairly thick bush.

We were also aware that we had the additional gamble that a thick branch could detonate our outgoing shell. But then they had the same problems,” the lieutenant explained. It was the Angolan tank’s ground support unit that first spotted the South African IFV as they maneuvered past – and that’s when training paid off. All the infantrymen started jabbering in Portuguese and gesticulating simultaneously, each trying to tell the T-54 commander where the Ratel was hiding. Confusion reigned. The enemy tank stopped, started again, reversed, and finally turned its’ turret toward the clump concealing the Ratel. And then – wham! One shell from the South African 90mm gun ripped into the Angolan tank’s lower turret area, and the short-lived IFV-versus-tank battle was over.

PT-76 tank taken intact during Operation Protea. These are beginning to see heavy service with MPLA and Cuban forces in Angola

A second tank was also destroyed that morning, this time a T-34. Its lone occupant, deserted by the rest of the crew after the first fracas, tried desperately to load, aim and fire the 85mm gun. It was a valiant attempt, and the FAPLA tanker even managed to fire one shot before a 90mm shell blew him away. Clearly the South Africans enjoyed two advantages in this and other encounters against Soviet hardware in Angola, even though these are marginal when compared to the armor and armament which are an integral part of conventional Soviet tanks. Aside from the quality of training, the South Africans have mobility on their side, and their Ratels and Elands offer a lower vehicle profile – both essential facets in Third World warfare. At the same time, it’s becoming more of an acceptable axiom that any moderately armed vehicle which gets the first accurate shot away will win the fight – especially in the thick African bush. Infantry support troops simply can’t maneuver in massed formations and provide the protective screen for their armor that close-in, vision-obscured fighting demands. The armor crew, be it Ratel or T-55, who takes advantage of this bare-knuckles bush warfare and reacts first will live to shoot another day. More important than this, however, is the critical aspect of training and leadership – especially at the junior commander level.

SADF troopies inspect Soviet T-34 captured intact during Operation Askari.

When separated from their Soviet, Cuban or East German mentors, Angolan FAPLA troops have shown a tendency toward poor shooting and retrograde operations. The South Africans – and the Israelis in their own sphere of ops – generally don’t have this problem. At the same time, though, the South Africans haven’t had it all their own way. During Operation Askari in January 1984 a South African Ratel troop carrier drove into a minefield, setting off a TM-57 land mine which crippled the vehicle. An Angolan T-54 nearby had more than enough time to pump a shell into the vehicle, killing everyone onboard. Another Ratel was also knocked out a few years previously during Operation Smokeshell, when it took a salvo from a 14.5mm anti-aircraft gun. Similar rounds hitting any one of the Soviet MBTs would have glanced harmlessly off the shell. The South Africans are the first to admit that, so far, they have been fortunate.

Most of their successful ventures in the tank versus light armored vehicle saga have been as a consequence of ambushes. Overall they have fared well, but Pretoria concedes that the Angolans have learned a few lessons about armored warfare. For this reason they wouldn’t like to use the likes of Ratels or Elands again – preferring the heavier Olifant MST – should they ever need to face Russian tanks once more. For the time being, the South Africans have updated the chapter on tank killing in the ’80s. Theirs is the first soft-skinned force in modern warfare to haye challenged tanks – and come out on top.

SOF Magazine JULY 86 – Al J. Venter